By Pau Basilia, Timothy Ong, Alyssandra Lopez, Christian Fernandez, Quincy Lingao, Marvin Dorosan, Salvador Sambitan III, and Grace Barretto-Tesoro

The Pata Church ruins, officially called ‘Nagsimbaanan’ stand in disrepair. Housing and development surround the abandoned church that garners only infrequent visits from devotees on holy days. A high traffic road borders the south, while a small cottage for the caretaker sits on its southwestern edge. To the north, a handful of houses has transformed the land in the last century, while its eastern side still opens to a tributary of the Pata River.

The Archdiocese of Tuguegarao still holds ownership of the land, which prevented further interference from developments. However, Pata Church has seen its fair share of treasure hunting activities that displaced much of the church interior. To prevent further damage, and, possibly, to reinvigorate local recognition of the church, the Archdiocese was more than happy to welcome the archaeological research team from the University of the Philippines School of Archaeology (UPSA), headed by Dr. Grace Barretto-Tesoro. She is joined by Dr. Pau Basilia Architect Timothy Ong, UPSA staff Arcadio Pagulayan, and graduate students from UPSA: Alyssandra Marie Lopez, Christian Fernandez, Quincy Lingao, Marvin Dorosan, and Thirdy Sambitan. We were later joined by Dr. Emil Robles (UPSA). This fieldwork, running from the 6th to the 20th of July 2025, is a collaboration between Dr Patrick Roberts who heads the Pantropocene Project hosted at the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology, UPSA, Provincial Government of Cagayan through the Cagayan Museum and Historical Research Center, Archdiocese of Tuguegarao, University of Saint Louis Tuguegarao, and the Municipal Government of Sanchez Mira.

Our team’s primary objective is to examine the impact of Spanish colonisation on land use in the Philippines. In 2022, a team led by Barretto-Tesoro (et al. 2023) documented 26 Spanish colonial structures, including churches and church complexes, and kilns, which were recorded under 21 National Museum site codes. After conferring with Dr Regalado Trota Jose, current Commissioner of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, we selected the Pata Church Ruins, officially the Nagsimbaanan Site (National Museum code II-2022-J4) due to the limited archival evidence on this specific church. We also oaimed to look for pre-Spanish deposits that would generate data on their way of life. Further, we pursued to understand how people in the past interacted and transformed the landscape through time.

Church Complex

Little archival information is available for Pata Church or Nagsimbaanan. Local legend places Nagsimbaanan as possibly one of the last resupplying outposts for missionaries bound for Japan and China or other nearby territories. Prior to the arrival of the Spanish friars, communities would have utilised the coast for trade and exchange with foreign merchants, and used Pata river, including its tributaries, to transport those goods inland. A small tributary, connected with Pata River, would have been utilised for travel of people and goods. However, there are few instances where Nagsimbaanan appears in archival records. From available literature, Pata Church was built in 1595 by the Dominicans under the supervision of Fray Gaspar Zarpate and Miguel de San Jacinto (Priory of the Mary Magdalene) using wood materials and was later replaced with much sturdier stone materials. Based on old maps, the church was already in ruins and abandoned in the 1890s. The church complex has a north to south orientation with a main church, a belfry attached to the southwest, a sacristy to the east, and a convent attached on its eastern wall. The sacristy opens to the courtyard, which is closed off to the east and south by two separate convent structures. The southern convent has two smaller rooms of unknown purpose tucked into its north wall. The main church has a nave flanked by two aisles separated by possibly 20 columns.

There are three possible phases of construction throughout the lifetime of the church. The first construction phase of the church is likely a structure made with light materials. Subsequent construction activities have erased traces of the oldest phase. The next construction phase of the church used only stone with, possibly, light mortar. The northwest buttress of the altar is the only evidence left within the church of this second phase. However, the same building technique was used for the convent walls. Some smaller areas of the convent walls contained roof tiles that could have been installed at a later repair phase coinciding with the third phase of the church. The last construction phase of the church used brick cladding infilled with rubble (i.e., bricks and stones in lime mortar). Further additions occurred more recently, including the concrete grotto, concrete cladding, and a smaller altar for the Virgin Mary within the main altar (Figure 1).

Trenches and Test Pits

We opened five trenches and two test pits ranging from 1m x 2m to 3m x 2m. We placed the trenches and pits at strategic sections that investigated different spaces inside the church complex. Test pit 1 (1m x 2m) looked for remains of the missing church façade in the structure’s main interior. No structures were found, suggesting that the façade was aligned with the belfry south walls. We also exposed two graves approximately 200m below the surface. The human remains were poorly preserved, but we were able to retrieve the lower appendages of two individuals. A second test pit (also 1m x 2m) was opened to investigate the convent exterior, which was believed to have been a garden for the priory.

Trenches were opened within the church complex structures. Trench 1 was placed on an opening at the south wall of the convent. Two steps made with cut stones, bricks, and lime-mortar were uncovered. This indicates that the convent was accessible through the southern extent of the church complex. Trench 2 investigated a column base to gain a better understanding of construction methods. The foundation of the brick column were large cut stones supplemented by smaller cut stones. Under the column base, human remains were discovered at a similar depth with Test Pit 1, only 25 meters away. Trenches 3 and 4 were placed within the convent grounds. Investigations in Trench 3, placed in the sacristy, revealed brick flooring attached to the interior wall adjacent to the main church structure. While there were no structures found in Trench 4, many artefacts and construction or destruction debris were recorded. This suggests that the area north of the southern interior wall was possibly a courtyard. Similar to Trench 3, investigations in Trench 5 revealed brick floors and a circular brick feature with a filled-in centre that was next to an interior wall.

Artefacts

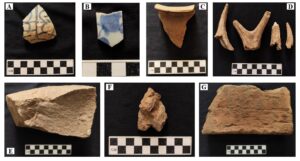

Artefacts were collected throughout the excavation and through sieving (Figure 2). Most of the finds were construction or destruction debris consisting of various brick types and lime mortar. Bricks consisted of wall bricks, floor bricks in two colours. We also recorded roof tile fragments. We also found a large amount of earthenware pottery fragments and porcelain sherds dating to the 15th century through to the 19th century. Unlike earthenware, porcelain objects are not locally made. They are incorporated into local lifeways through trade and exchange. Possible stone tools were also collected. All collected materials were brought to the UPSA laboratory for further analysis.

Auger and Stratigraphy

Auger testing was conducted in Trench 4 and Test Pit 2, both of which have reached sterile layers. The auger is a drilling tool that takes small samples of subsurface deposits to aid in understanding stratigraphic layers. In Trench 4, the auger testing resulted in three sediment layers. In Test Pit 2, augering was carried out after reaching 183cm below the surface and it also resulted in three sediment layers (Figure 3).

In photo: Arcadio Pagulayan and Marvin Dorsan in Test Pit 2.

Landscape use through time

The church complex sits on a promontory of the Pata River. It is located at the river delta where Pata River lies to the west and a tributary to the north. Interestingly, the second phase of the church also transformed the lower promontory it sits on. Evidence of colonial shoring from all sides of the church was evident from a close proximity to the church and towards the river. This would have created terraces for various activities, such as gardens or storage spaces. We do not know yet whether these structures were built before or together with the church or were subsequent additions. Additionally, low walls extend to the east from the church complex. This could create a boundary or a protection against outsiders. These additional structures (i.e., walls and shoring) that supported the church complex are transformations that had a lasting impact on the landscape.

An Altar’d state

After years of neglect, immediate action should be taken to preserve the Pata Church Ruins. We recommend short-term and long-term solutions. Metal support and braces should be installed to support the walls and posts of the exterior section of the altar wall. For the long-term solution, guidance and advice of relevant specialists could greatly aid in the preservation of the ruins. Local stakeholders could consult agencies, such as the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, and heritage architects who would be able to provide detailed plans. Importantly, participation of locals is paramount. They are encouraged to maintain church grounds, such as avoiding using the area as a garbage dump. Proactive heritage management could ensure the preservation of the ruins for future generations of Cagayanos and for Filipinos to have the opportunity to appreciate one of the oldest Catholic churches in the Philippines.

Acknowledgments: Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology, Governor Edgar B. Aglipay and the Provincial Government of Cagayan through the Cagayan Museum and Historical Research Center, Mayor Abraham Bagasin and the Sanchez Mira Municipal Government, University of Saint Louis Tuguegarao, Archdiocese of Tuguegarao, Barangay Captain Belman Abon and the Sangguniang Barangay of Namuac, CMHRC Curator Niño Kevin Baclig, Sanchez Mira Tourism Officer Carla Pulido Ocampo, Sanchez Mira Tourism Staff Kyla Doming, Namuac Kagawad Avelino Ganiban, Namuac Kagawad Sheil, Imatong, Namuac Kagawad Levie Malto, Dr Caroline Marie Q. Lising, and Dr Raul Ting.

Team Details

UPSA Excavation Team: Grace Barretto-Tesoro, Pauline Grace Basilia, Marvin Dorosan,

Christian Fernandez, Joan Quincy Lingao, Alyssa Lopez, Timothy Augustus Ong, Arcadio

Pagulayan, Emil Charles Robles, and Salvador Sambitan III.

Excavation volunteers from CMHRC: Niño Kevin Baclig, Paul Agustin, Yeng Balatico,

Ramon Caranguian, Jake Coballes, Renato Cue, Geraldine Esguerra, Tricia Anne Jade Laborera,

Davin Edjae Lacambra, Megan Javier, JP Mabasa, Edward Obsequio Jr., Anthony Paul

Paddayuman, Joshua Jewel Palolan, Jan Raymundo, and Samuel Reyes. From USLT: Michael

Tabao, Prince Wilson Macarubbo, Kate Caranguian, Marianne Manicad, Garry Balintec

Reference:

Barretto-Tesoro, G., M. Mabanag, K. Baclig, M. Tabao, C. M. Q. Lising, L. Neri, and P. Roberts. 2023. Archaeological Survey in Cagayan Valley, Northern Philippines as part of the PANTROPOCENE Project. Proceedings of the Society of Philippine Archaeologists 12:99-118.