By Raisa Perez, Joan Quincy Lingao, and Mark Mabanag

Introduction

On 13 February 2023, we started the first archaeological excavation related to the PANTROPOCENE Project. The researchers associated with PANTROPOCENE aim to produce high-resolution data using a swath of analytical methods that can inform us about the effects of pre-colonial and colonial land-use strategies on tropical environments across the breadth of the Spanish Empire.

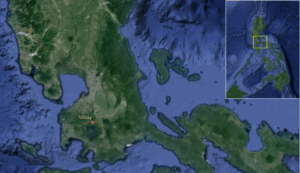

The Balai Isabel Ruins is a Spanish-era stone structure located within the Balai Isabel Resort in the town of Talisay (Fig. 1) in Batangas. Talisay is a town located in the north coast of Taal Lake, where an active volcano of the same name sits. While standing walls were clearly visible, archaeological remains were unknown until landscape workers accidentally exposed human remains. The National Museum of the Philippines (NM) was called in for assistance, and an official assessment study was initiated in 2011.

Aside from five human burials recovered, the NM archaeology team also found an adobe structure and what appears to be plaster flooring. Excavations at Balai Isabel were concentrated on the southern end of the stone structure. Information gleaned from historical texts reinforced the idea that the ruined structure was once the Old Tanauan Church when Talisay was only a component barrio of old Tanauan until the late 1800s. Vitales et al. (2011) suggests that the presence of burials at Balai Isabel point to the possibility that people who moved into the area still viewed the old church as a sacred site.

The members of the excavation team included Dr. Grace Barretto-Tesoro, Mark Mabanag, Quincy Lingao, Dr. Emil Robles, Raisa Perez, Ara Mariano, and Arcadio (Cads) Pagulayan, all from the University of the Philippines School of Archaeology (UPSA). Dr. Kim Plomp and Dr. Juan Rofes, both also from UPSA, came in for visits to observe and consult. Taj Vitales of NM, who led the excavations in 2011, and also a Ph.D. student at UPSA, came in for a few days to assist us as well.

In the following, Quincy, Raisa, and Mark provide their perspectives on the different phases of the archaeological fieldwork.

Pre-excavation

Raisa: A week before the excavation, the team had a meeting to discuss the history of the site, to divide tasks among the team, and to make final preparations. I was tasked with designing a tarpaulin that would display the important details of the site and outline the objectives for opening the site a second time for archaeological research (Fig. 2).

Quincy and I gathered all the necessary equipment required for our three-week excavation. Most of the equipment we needed was standard for archaeological excavations in the Philippines. This included our primary surveying tool, the theodolite, as well as ground-breaking equipment such as shovels, spades, and our favorite, the bareta (a digging bar). We brought pails for hauling the sediments that we would excavate, fine mesh strainers for sifting through the excavated materials, ranging poles, northing arrows, trowels, and brushes. These tools were essential for accurately documenting and analyzing the archaeological features and artifacts we would encounter during the excavation process.

Quincy: This excavation was my first fieldwork since I did my field school in 2022. I have never joined any excavations prior to this, so everything felt new to me. In the days leading up to the excavation, I worked on preparing the materials and equipment we needed to bring to the site. I had to prepare a detailed inventory to keep track of everything. Since this was my first fieldwork, I had to quickly go through the recording forms to familiarize myself with them.

Mark: One of the tasks I was assigned was to connect with the Talisay Municipal Office to inform them of our plans to excavate at the Balai Isabel Ruins. We were also trying to set up an appointment for a courtesy call visit to explain what we do in an archaeological dig as well as to convey the purpose of our work to their community. This is a necessary step. A few times for this project alone, we were able to find field guides and helpers through national and local government workers. For the excavations at Balai Isabel, however, we were able to find helpers through the help of resort management.

Excavation

Quincy: Mark and I were initially assigned to excavate a 2×2 m trench (Trench G) located outside of the church ruins. We plotted Trench G almost abutting the south wall of the stone structure (Fig. 3).

Mark: But even before we touched a grain of dirt, Grace had Cads perform an alay (offering) the day we arrived at Balai Isabel. It is a ceremonial practice to ward off evil spirits. The practice can be traced back to pre-Hispanic times. Cads took a bottle of gin and poured the liquor in the general areas where we were going to plot our trenches (Fig. 4).

Taj had planned to excavate in the same location of our first trench had there been another field season after 2011. He wanted to expose alluvial deposits that were caused by massive floodings in 1752. Hargrove (1991) asserts that this event pushed the residents to relocate their town further east to where present-day Tanauan is now situated. I also wanted to locate an archaeological square outside the stone structure as well. As I was also going to collect archaeobotanical samples in Raisa and Ara’s trench, I wanted to do an intra-site comparison to see if there are any differences in the assemblages within a known structure as opposed to an open area, especially when I got to the specimens from the lower ends of the stratigraphy.

Raisa: My trenchmate Ara and I opened a 2x2m trench (Trench F) adjacent to one of the buttresses on the western wall of the church ruins. During our pre-excavation meeting in Manila, our team had agreed to swiftly dig through the surface layer, reaching a depth of 70-80cm, in order to access the burial layer previously excavated by the National Museum in 2011. Our initial noteworthy discovery within the trench was a flat surface connected to the buttress. Initially mistaken for the church flooring, it turned out to be a part of the buttress itself (Fig. 5). Another significant find that slowed down our excavation progress was the remains of the buttress that had seemingly collapsed towards the east, into Trench F, potentially due to either an earthquake that had struck Talisay or tremors caused by an eruption from the nearby Taal Volcano.

Mark: The area where Trench G was plotted had been heavily disturbed by backhoe digging when the property owners were attempting to do some landscape improvements. Through the first few days of our fieldwork, workers at Balai Isabel would inform us of this. They also added that they had also dug inside of the stone structure. True enough, we were still unearthing modern materials past the 2-meter mark below the surface. This mixing is also evident in Trench F. One time, I was informed by Grace that a layer that I had already processed for archaeobotanical sample extraction was a disturbed layer. They found a piece of copper wiring within the lower reaches of the layer.

Quincy: Our goal was mainly to find some botanical and zooarchaeological materials for our own research. I personally hoped to find animal remains for my thesis. Unfortunately, our first trench only yielded modern materials such as a plastic comb and a water bottle. Before closing the trench, however, we decided to perform auger testing on the terminal excavated layer of the trench. We wanted to confirm the absence of any artifacts in layers below this layer. Regardless of the lack of archaeological materials, we still recorded everything, including the stratigraphy of the trench.

Raisa: The stone feature consisted of large, well-cemented cobblestones that formed a consolidated structure. Beneath this layer, we uncovered additional cobblestones that were relatively like the ones above, but lacked cementing. This suggested the possibility of two separate events causing the ruin of the buttress: one earlier event that had weathered the limestone cement holding the cobblestones together, and a later event closer to the present, where the cobblestone cement had not yet fully weathered (Fig. 6). To facilitate the excavation process, we extended the trench first by 50cm to the east. Still, we had to expand a further 150cm eastward to provide more room to maneuver, as the cobblestones posed a challenge.

Upon removing all the cobblestones, we had excavated a total trench area of 200 x 400 cm. We also uncovered several square nails, as well as porcelain and earthenware tiles, likely remnants of the aggregates of the lime mortar used in constructing the walls and buttress of the church.

Quincy: Mark and I decided to open another trench (Trench H), this time inside the ruins. We did systematic auger testing (Fig. 7) every 5 m from the north wall of the church ruins to determine the location of our new trench. We decided to place our trench approximately at the longitudinal center of the ruins. This time, we were able to successfully reach the archaeological layer after recovering several fragmented bricks and pieces of porcelain sherds.

Mark: Of the five auger holes we initiated, we decided to locate our 2×2 trench in the area of the third auger test. We chose this location because we were able to reveal a sediment matrix consisting of clayey sand at around 250 cm. We determined that this layer may be older than the burial layers that were exposed in Trench F.

Raisa: On the fifth day of excavation, a worker from Trench F hurriedly approached us, presenting the first human bone discovered that season—a medial phalanx! This discovery ignited excitement within the entire team, renewing our energy to continue excavating Trench F. Subsequently, disarticulated human bones, interspersed with occasional animal bones, were found throughout Trench F. Eventually, we unearthed the initial set of articulated human feet right by the southern wall of the trench. This indicated that the remaining bones of this individual were likely located in the un-excavated southern section of the trench.

Continuing our excavation efforts, we came across three more sets of articulated human feet at nearly the same depth and position as the first individual, with their remaining bones awaiting discovery in the un-excavated southern portion of the trench. To streamline our progress and facilitate mapping, Emil pitched his Leica Disto X4 with a Disto X360 attachment to our trench. This device enabled us to record the X, Y, and Z coordinates of each bone found, simplifying the mapping process with a simple push of a button. In the afternoons too, Emil would do photogrammetry of the trench which made mapping the trench a breeze.

Mark: The layers at Trench H proved to be disturbed as well. This was clear to see in the upper layers, especially. Up to at least 1 meter below surface, we recovered modern materials such as a PVC pipe fragment and an instant noodle cup container. Further down, at about 150 cm, we exposed a layer with rubble, a few large cobbles, and mortar may be coeval with the church ruins. Starting from the layers below this, I began collecting sediment samples for archaeobotanical analysis. I also collected samples for phytolith, pollen, and stable isotope analysis. While the default method of collecting pollen samples in archaeological trenches is through a vertical column, mixing of the layers at Trench H precluded me from doing this. I instead employed a “contextual sampling” approach. I only targeted layers that we had determined to have not been disturbed. I employed the same method for my archaeobotanical subsamples. I did the same at Trench G. Excavations at Trench H reached a maximum depth of more than 2 meters below surface.

Raisa: After nearly two weeks, we had to conclude our excavations even though more bones were still being uncovered. Before proceeding with backfilling, Mark entered the trench to collect soil samples from crucial layers for testing, while Ara and I gathered soil samples to conduct Munsell and soil descriptions. During the backfilling process, we took care to avoid damaging both the human bones that were left uncollected and the remaining church structures.

Post-excavation

Mark: The excavations at the Balai Isabel Ruins was the first of what we hope to be many for the PANTROPOCENE Project. It is a good first step. I was able to collect some samples for my archaeobotanical analysis as well as for stable isotope, pollen and phytolith studies. I feel a bit disappointed though. We were excavating methodically and were very careful in separating the layers to maintain the integrity of the context of the finds. Because of this and the layers at the site being disturbed and insecure, I am doubtful that we were able to reach the target age range of 2000 BP.

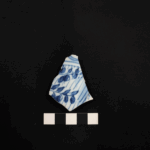

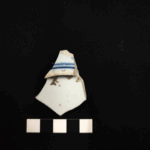

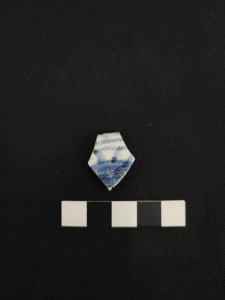

Quincy: We proceeded with the accessioning of the artefacts we recovered from the site when we got back to UPSA. Raisa and Ara worked mainly on the human remains, while I accessioned the rest of the artefacts. We accessioned around 180 ceramic sherds from Trench F and around 21 sherds from Trench H. The sherds consist of earthenware and stoneware sherds, as well as tradeware ceramics such as celadon and blue-and-white porcelain (Figs. 8 and 9). Several fragments of bricks and roof and floor tiles were recovered from Trench F and Trench H. Three square nails possibly associated with the construction of the church were also recovered from Trench F.

Very few faunal remains (at least 10 pieces) were recovered from the site, all of which were from Trench F. It is currently unlikely that these will be included in my ongoing study, which is quite unfortunate. Many shells were recovered from the site, but these were more associated with the construction of the church based on the traces of lime mortar on them.

Raisa: After two weeks in the field, we finally headed home to UPSA and stored the artifacts that we excavated. Ara and I were tasked to accession the human bones and teeth (Fig. 8) that were found in Balai Isabel. All the bones were properly packed in ziplock bags and then in bubble wrap and were all stored in a plastic storage box. This box was stored in the Osteoarchaeology Laboratory of UPSA.

Ara, Quincy, and I began cleaning and accessioning the human bones a few weeks after the end of the excavation. We started sorting the bones into their proper contexts and then started identifying the diagnostic bones or the bones that were complete enough to identify. We found several long bones, so those were the first ones to be accessioned. Eventually, we had to sort out the non-diagnostic bone fragments from the complete bones so that we could do further identification and possible future testing on the complete bones. We also separated the articulated bones, providing us with the opportunity to reconstruct the individual’s skeletal structure when we return to Balai Isabel to retrieve the remains found in the southern area of Trench F.

As we documented and preserved each bone, we came to realize the importance of our work. The human remains we carefully accessioned could provide valuable insights into the lives of those who lived at Balai Isabel centuries ago. The work of archaeologists at UPSA is a testament to our commitment to preserving our shared heritage, ensuring that it endures for generations to come.

References

Hargrove, T. R. 1991. The Mysteries of Taal: A Philippine Volcano and Lake, Her Sea Life and Lost Towns. Manila: Bookmark Pub.

Vitales, T. J., Bautista, R., Pagulayan, P. 2011. Report on the Archaeological Excavation of the Spanish Period Colonial Ruins in Club Balai Isabel, Talisay, Batangas (28 February – 19 March 2011). Manila: National Museum of the Philippines.